Tribunals and Ombudsmen

Tribunals

Beyond Judicial Review

⇒ Judicial review is excellent in respect of a finite number of areas where the courts feel confident to intervene:

- Jurisdictional excess;

- Error of law;

- Wednesbury unreasonableness;

- Proportionality review

- Procedural fairness.

⇒ But the courts are reluctant - and perhaps for good reasons - to intervene in some decision making:

- Where deference is due;

- Where the merits of the case are at issue;

- Where Parliament (by an Act, or otherwise) promotes a particular course of action.

⇒ As an addition to judicial review, not a replacement for it, administrative tribunals have become commonplace in English administrative law since around the first half of the twentieth century.

- Tribunals provide, in limited circumstances, the opportunity for claimants to seek administrative redress.

⇒ But this does not mean that tribunals solve the problems or limitations of judicial review just identified.

- With the Parliamentary Ombudsman, tribunals have a limited but important impact on improving the availability of administrative justice - upholding the values of good governance, legality, and fairness

Tribunals – What Are They?

⇒ Tribunals are statutory bodies of administrative redress, where decisions of other public bodies can be ‘appealed’ (not reviewed), including on the merits of the decision.

- A tribunal may also have jurisdiction to decide matters as the ‘primary’ decision-maker - for example, the Gender Recognition Panel Tribunal certifies a transsexual person’s gender.

⇒ But the powers of tribunals will be only those powers conferred to it by statute. If a tribunal exceeds its statutory powers, like any other public body its decision may be quashed by the Administrative Court in judicial review

⇒ Although formally the same as other types of public body, tribunals are in other respects different.

- Often tribunals will have considerable powers in respect of questioning the merits of another decision-maker.

- Often (but not always) they will look a lot like courts in respect of their presence, procedures, and formality.

- Often (but not always) a decision of a tribunal may be subject to the appellate jurisdiction of another tribunal.

⇒ There were two major legal changes to the law on tribunals.

- Following the Franks Committee (1957), the Tribunals and Enquiries Act 1958, as amended and supplemented in 1971 and 1992.

- Following the Leggatt Report, the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007.

The Franks Report and the 1958 Act

⇒ Sir Oliver Franks chaired a committee examining the state of administrative law following the ‘Crichel Down Affair.’

⇒ On tribunals, Franks was keen to regularise and formalise the workings of tribunals, identifying the need for openness, fairness, and impartiality. He wanted to make them more like courts.

⇒ He proposed a Council on Tribunals, to be presided over by a President, to help secure the regularisation of tribunals.

⇒ But the Franks report was mainly aspirational, and the subsequent Act was of limited effect (compared with the 2007 Act).

⇒ The Franks Report dominated thinking on tribunals for the next few decades. Perhaps its effects were seen over time (in practice). But a new legislative regime was sought in 2001, when the Government commissioned a new report from Sir Andrew Leggatt.

The Leggatt Report and the 2007 Act

⇒ Taking what Frank had aspired for, but perhaps being a little more concrete as to what legal change would be needed, Leggatt proposed that most important tribunals should be placed under a single tribunals structure (National Tribunals Service) and sponsored by the Ministry of Justice.

⇒ In order to achieve consistency amongst the tribunals, procedural matters would be decided centrally, with a desire to provide for a more formal hearing.

- Also, with resources pooled into a single service, tribunal judges (whose training would become regularised too) could decide on cases across several areas

⇒ Individual tribunals would become part of a single ‘First Tier Tribunal’ structure, with an ‘Upper Tribunal’ providing an appellate jurisdiction.

- The service and structure would provide for a greater level of transparency, consistency and efficiency.

⇒ Perhaps because of this, or perhaps for other reasons (austerity?), the use of tribunals has grown massively in the last few years.

- The main tribunals under the ‘First Tier’ and ‘Upper Tribunal’ headings received a total of 739,600 cases (to 2012), with 2010-2011 being the busiest year to date at 831,000 cases

Statistics

⇒ If we compare these figures with judicial review, the picture is striking.

⇒ The Administrative Court hears around 11,200 cases per year, but many of these are statutory rights to review akin to common law judicial review.

- Many of these applications won’t receive a full hearing (permission to JR refused).

- Of those that are granted permission, very few succeed. In 2011, only 174 cases resulted in a remedy - usually a quashing order

Statistics - Why the difference?

⇒ Tribunals are cheap — sometimes free.

⇒ Tribunals are relatively informal (less so under the 2007 Act), and so claimants often represent themselves.

- The tribunals accommodate this rather well—they are sometimes more inquisitorial than the courts, and they can assist claimants more readily since tribunals regularly decide on similar cases within a definite area or domain

⇒ Also, tribunals are not simply aiming at questions of jurisdictional excess or procedural fairness: there will often be many different grounds for an appeal to a tribunal - including on the merits of a decision.

⇒ The tribunals system is the workhorse of administrative law - at least in terms of access and the number of cases

2007 Act: Appeal and Review

⇒ The 2007 Act provides for two tiers of tribunal (‘First Tier’ and ‘Upper’ Tribunals)

- The Upper Tribunal may hear an appeal against the decision of the First Tier Tribunal

- This helps to achieve the regularity and consistency strived for in the Leggatt Report (and perhaps the Franks Report too

⇒ By Section 9, the First Tier Tribunal may review its own decisions on its own initiative

- If it decides to set aside a decision it has made, it must either re-make that decision or refer the matter to the Upper Tribunal—s.9(5)

⇒ Section 11 provides for a right of appeal from the First Tier Tribunal to the Upper Tribunal on a point of law

⇒ An appeal lies from a decision of the Upper Tribunal to the Court of Appeal on a point of law (Section 13), except where the decision of the Upper Tribunal is an ‘excluded decision’ (a decision where no appeal lies to the Court of Appeal)

- Under s.13(8)(c), an ‘excluded decision’ includes a decision of the Upper Tribunal to refuse permission to hear an appeal to it.

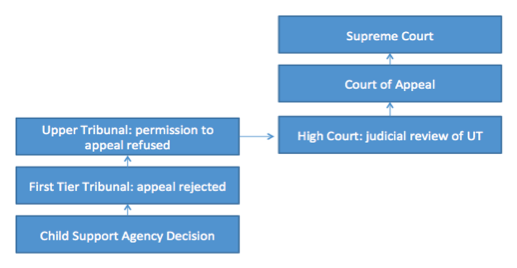

R (Cart) v Upper Tribunal [2011] UKSC 28

⇒ The Upper Tribunals (which hears appeals from the First-Tier Tribunal) refused two claimants permission to appeal to it. The claimants sought judicial review of this refusal

⇒ The Administrative Court, the Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court all rejected the claim in judicial review - but for different reasons…

⇒ The Administrative Court ruled that decisions of the Upper Tribunal were not amenable to judicial review at all, because the Upper Tribunal was an alter ego of the High Court

⇒ The Court of Appeal thought otherwise: they said that the Upper tribunal not alter ego of the High Court and so could in principle be subject to judicial review. However, it was within the lawful discretion of the Upper Tribunal to refuse permission to appeal

- So they said, in effect, that the Upper tribunal would only be reviewed on a pre-Anisminic basis e.g. jurisdictional error

⇒ The Supreme Court took a different approach: the Upper Tribunal's decisions may be judicially reviewed, but only if the review poses an important point of principle or practice, or that there is some other compelling reason to hear the case in judicial review

The Legal Problem in Cart

⇒ Because the Upper Tribunal refused permission to hear an appeal to it, it cannot (by statute) be a decision that can be appealed to the Court of Appeal (i.e. an ‘excluded decision’)

- Therefore, Mr Cart’s journey for administrative redress ended with the Upper Tribunal’s refusal to hear an appeal to it

⇒ Therefore, Mr Cart sought to judicial review of this refusal, which went initially to the High Court, then to the Court of Appeal, and finally to the Supreme Court

The Art of Getting a First in Law - ONLY £4.99

FOOL-PROOF methods of obtaining top grades

SECRETS your professors won't tell you and your peers don't know

INSIDER TIPS and tricks so you can spend less time studying and land the perfect job

We work really hard to provide you with incredible law notes for free...

The proceeds of this eBook helps us to run the site and keep the service FREE!

Cart: The Supreme Court

⇒ The decision (of the Supreme Court) was to provide for the judicial review of the Upper Tribunal’s decision to refuse permission to appeal to it (or any of its decision-making), but not on the usual bases for judicial review: for judicial review to take place by the High Court, there must be an important point of principle or practice raised, or there must be some other compelling reason for the judicial review

- Lady Hale said if judicial review of the Upper Tribunal’s decision were restricted beyond this, there would be “a real risk of the Upper Tribunal becoming in reality the final arbiter of law”

⇒ However, the requirement of an important point of principle or practice, or other compelling reason, might make judicial review impossible in practice

- This is a high threshold to meet

- In practice, the Upper Tribunal will routinely be the ultimate arbiter of law

- It may be possible that the Upper Tribunal would make an error of law which goes uncorrected by the courts (because it doesn’t meet the threshold)

⇒ Throughout Lady Hale’s speech, the reason for this approach is undoubtedly linked to Parliament’s intention in enacting the 2007 Act

- Parliament had intended, by creating the Upper Tribunal and empowering it as it did, for it to routinely exercise an appellate jurisdiction and to build precedent (rules, processes, tests) in the administrative field

⇒ Perhaps this position of the Upper Tribunal (unique in the administrative field) is legitimised by the Act itself

- Section 15 gives the Upper Tribunal jurisdiction to exercise a judicial review function - with the availability of those remedies normally preserved for the High Court (mandatory order, prohibiting order, quashing order, declaration, injunction).

Judicial Review by the Upper Tribunal

⇒ But Section 18 imposes a condition upon the exercise of the Upper Tribunal’s judicial review powers

- The Upper Tribunal must be presided over by a High Court judge (who would ordinarily have the authority to exercise judicial review powers in the High Court).

- It nevertheless strengthens the position of the Upper Tribunal and confirms its status as a unique decision-maker.

⇒ A further condition on the UT’s ability to conduct judicial review is provided by s.18(6): the Lord Chief Justice must make an order prescribing the applications which might be heard by the Upper Tribunals for judicial review

- Exercising such a power, the Lord Chief Justice made a designation on 21st August 2013: all immigration cases except those of a type listed in a set of exceptions could now be heard in the UT on judicial review grounds.

- The High Court would continue to hear immigration cases questioning the validity of primary or delegated legislation (including s.4 HRA); challenges to unlawful detention; and a couple of other discrete challenges - e.g. a challenge to a decision of the UT itself, or SIAC. BUT, all other immigration-based judicial reviews could be heard by the Upper Tribunal

Tribunals Today

⇒ What is evident in the 2007 Act and the decision in Cart is that tribunals are becoming a lot like courts.

- This is not how they were envisaged when they emerged at a time when the State was expanding; they were an informal, accessible and cheap way of seeking redress

- Today, tribunals are encouraged (by the 2007 Act, the HRA, and culture generally) to move towards procedural regularity, working under a body of precedent, and undertaking court-like functions

⇒ It is notable that tribunals are hearing an increasingly high number of cases

- For every application for judicial review, tribunals hear 80 cases.

- If tribunals are becoming more like courts, and case numbers are continuing to rise, there are resource implications

- The Government is not interested in increasing the use of tribunals generally—quite the opposite. In the 2010 cull of quangos, several tribunals were abolished

⇒ The Government is also making tribunals more ‘streamlined’ by looking at changes that can be made to procedure, grounds, and so forth

- Mr Justice Underhill recently reviewed tribunals on behalf of the Government—specifically how the Employment Tribunal (one of the largest by case load) might better and more easily reject more cases as disclosing no realistic prospect of success, or on some other basis

Parliamentary Ombudsmen ('PO')

Introduction

⇒ Around 90 countries have ombudsmen

⇒ An ombudsman is empowered to investigate complaints. Usually this is in respect of the State and its agencies, but private sector ombudsmen also exists

- A recent example of the latter includes the Legal Ombudsman, who hears complaints about the legal profession, and has powers to award compensation

⇒ But the main administrative (that is, public law) ombudsman in the UK is the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman—an office created by the Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1967

- The PO is appointed for seven-year terms; the office is currently held by Dame Julie Mellor. The PO is an officer of the House of Commons

⇒ The parliamentary link is important in understanding the role of the PO. Following the ‘Crichel Down Affair,’ there was a concerted effort to improve the quality and fairness of public administration. The following 50 years saw:

- The High Court expand judicial review in cases like Anisminic, GCHQ, World Development Movement, etc.. (the courts)

- The extended use of tribunals, including their structural cohesion following the 1958 and 2007 Acts (tribunals are executive bodies)

- The introduction of the PO (an officer of the legislature)

Ombudsmen

⇒ Rather than focussing on claimant rights, jurisdiction, and due process (the court’s interest), or merits review through an appellate process (the tribunal’s interest), the PO is more broadly interested in maladministration in public life and governance.

⇒ This is reflected in the Act establishing the powers of the PO

- Under Section 5, the PO has the discretion to investigate any matter referred to them on the ground that there has been maladministration occasioning injustice

- But s.5(1) requires that a complaint from a member of the public must be referred to the PO via a Member of Parliament (MP)

⇒ Whilst the grounds for an investigation are broad, there are important exceptions to the PO’s general power to investigate

- S.5(2) limits the power to investigate by excluding those cases where a statutory or other right to appeal exists to a tribunal, or where some appropriate cause of action is available in a court of law (e.g. judicial review)

- Thus, we can say that the role of the PO is supplementary to the role and function of tribunals (appeals) and courts (review).

⇒ The MP ‘filter’ will also limit some cases - what if your MP decides not to refer the matter?

- The MP ‘filter’ affirms the parliamentary nature of the PO’s work: one doesn’t have a ‘right’ to an investigation. The PO’s work takes place in a political context, not a legal one

⇒ In carrying out an investigation, the PO has broad and inquisitorial powers

- The PO may, under s.8(1), summon the attendance of any public official, or any other person, or require the production of any documentary evidence in pursuit of the investigation

- The PO’s powers to summon witnesses is the same as a court’s

- To enforce this, Section 9 creates an offence equivalent to contempt of court for any person who obstructs the lawful exercise of the PO’s functions.

⇒ The PO can publish a non-legally binding report, which may make recommendations as to how to remedy the injustice suffered from the maladministration (including a recommendation of compensation)

⇒ Under s.10 (3) the PO has discretion to publish the report to the public, by laying a report before both Houses of Parliament where she thinks that:

- The injustice hasn’t been remedied, or

- Won’t be remedied

⇒ We see the PO is seen to act in the political sphere (publicity), not a legal one.

The Balchin Litigation

⇒ The leading case (in terms of the ratio) is R v Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration, ex parte Balchin (No.2) (2000) 79 P&CR 157

⇒ The petitioners complained that the Secretary of State for Transport was guilty of maladministration in confirming Road Orders without seeking an assurance from Norfolk County Council that the Balchins would be given adequate compensation for the effect of the road on their home. They now challenged the Ombudsman’s report, which had rejected their complaint, in judicial review proceedings

⇒ The judicial review was successful: in 1996 the decision of the PO not to investigate was quashed. In 1997, the PO reported on the matter once more, but again decided not to investigate. In 1999, the High Court quashed that decision. In 2000, the PO again reported on the matter, but again decided not to investigate. The High Court, in 2002, quashed that decision (for the third time!)

⇒ In Balchin (No 2), Dyson J was concerned that the PO made his findings without giving adequate reasons.

- The PO needs to state why he thought there was no injustice, or why he thought the question of injustice was irrelevant because there had been no maladministration. Without reasons “it leads to the reasonable suspicion that he failed to have regard to it at all, or that, if he did, his reasons for concluding that there was no injustice would not bear scrutiny.” (per Dyson J)

⇒ So Balchin advances two key legal points:

- What constitutes ‘maladministration’ and ‘injustice’ under the Act is broadly for the PO to decide;

- But in cases where there is apparent ‘injustice’ conceived of in the broader sense (including a sense of outrage), it is for the PO to state why he thought there was no ‘injustice,’ or why there had been no maladministration (thus ousting the injustice question).

Is the PO’s report legally binding?

⇒ Suppose the PO puts together a good and valid report, and publishes it to Parliament. Is it binding on the relevant Minister or official? We’ve already seen from the Act that it isn’t. But that hasn’t stopped the High Court from enforcing some aspect of the reportage.

- See, for example, R (Bradley) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2008]

R (Bradley) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2008] EWCA Civ 36

⇒ The Government issued guidance on pensions - guidance that was seriously flawed in that it created the impression that certain types of pension product were secure and well-funded, when they were not. The Government also changed ‘minimum funding requirements’ for such pensions, which only exacerbated the financial losses later experienced by the pension product holders.

⇒ The PO investigated the scandal and delivered a most damning report, alleging maladministration on the part of the Government occasioning serious injustice and considerable financial losses (losses have since been assessed in the £billions, not £millions).

⇒ The Minister rejected the report’s findings in its entirety.

⇒ In judicial review proceedings, the High Court confirmed that it could not enforce the recommendations of the report, since they were not legally binding.

- But, and somewhat creatively, it did find that the Minister’s rejection of the report’s findings was so unreasonable that no reasonable Minister could have so rejected the report in its entirety. The Minister had acted irrationally (i.e. Wednesbury unreasonableness).

- This is not the same as giving legal effect to the PO’s report → the court held that the Minister is entitled to reject the findings of the PO’s report and to account for his reasons for doing so. The Minister is entitled to prefer another view. But where the Minister rejects the findings of the report and fails to account for her position, the court is entitled to hold such a rejection irrational, where it is indeed irrational

⇒ Thus, the Court of Appeal held that the misleading information the Government published on the security of the pension products amounted to maladministration occasioning injustice, and that the Minister’s rejection of such a finding was irrational

- The Minister’s rejection of the findings were quashed → this doesn’t mean the report is legally binding in respect of the Minister’s obligations to provide a remedy to the victims or follow the recommendations of the report. Rather, the Minister must confront the report and either cogently say why the report’s are wrong (this would have to survive Wednesbury review), or to accept the findings of the report, but offer an alternative solution vis-à-vis the victims.

⇒ In other words, the Minister:

- Is not entitled to reject the findings of a PO report where it is irrational to do so; but

- May reject the recommendations of the report and prefer another view.

⇒ The outcome respects the important role of the PO in providing administrative redress, but affirms the idea that the PO’s functions operate within a political sphere, not a legal one.

Tribunals & Ombudsman

⇒ Our brief exploration into forms of administrative redress other than judicial review illustrates the desirability to have a ‘mixed’ administrative law system.

⇒ Judicial review has its limitations → tribunals offer cheap, informal, expert panels for hearing appeals of the substantive decision-making. The PO supports the workings of Parliament by bolstering the political processes of accountability.

Law Application Masterclass - ONLY £9.99

Learn how to effortlessly land vacation schemes, training contracts, and pupillages by making your law applications awesome. This eBook is constructed by lawyers and recruiters from the world's leading law firms and barristers' chambers.

✅ 60+ page eBook

✅ Research Methods, Success Secrets, Tips, Tricks, and more!

✅ Help keep Digestible Notes FREE