Express easements

⇒ The most straightforward in which X can acquire an easement over land owned by Y is by Y expressly conferring the easement on X.

⇒ Express conferral can occur in an ad hoc transaction e.g. Tim (owner of the freehold estate in Blackacre) grants Emily (owner of the freehold estate in Blueacre) a right of way over Blackacre.

⇒ Express conferral also occurs on the transfer of land e.g. Tim sells part of Blackacre to you and either:

- Grants (grant of an easement) an easement benefitting the land transferred to you and burdening the land retained by her, OR;

- Reserves (reservation of an easement) an easement benefiting the land retained by her and burdening the land transferred to you.

⇒ Legal or equitable:

- An easement is a right in rem which is capable of being legal (Law of Property Act 1925, section 1(1)).

- An express easement will actually achieve legal status if created with the requisite formality i.e. a deed (Law of Property Act 1925, section 52(1)) and registration (Land Registration Act, section 27(2)(d)).

- Where the relevant formality requirements are not satisfied, the easement may take effect in equity. It will do so if there is a valid (actual or discovered via Parker v Taswell (1858)) contract granting the easement (Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989, section 2).

Implied easements

⇒ Easements will be implied into a conveyance of land (whether that be a transfer of the freehold or a grant of the leaseholdld) on three different doctrines:

- (1) The doctrine of necessity.

- (2) The doctrine in Wheeldon v Burrows.

- (3) The doctrine contained in the Law of Property Act 1925, section 62.

(1) The doctrine of necessity

True necessity

⇒ The law impliedly grants (or reserves) an easement on a conveyance of land where the land transferred (or retained) is landlocked i.e. there is no access to the land → The easement implied is a right of way over the retained (or transferred) land.

⇒ An easemet won't be implied through true necessity if there is a contrary intention that the parties do no intend there to be access to the land (Nickerson v Barraclough [1981]).

⇒ The easement is not implied if there is a footpath, or even access by water, to the transferred land (MRA Engineering v Trimster (1987); Manjang v Drammeh [1990]).

Common intention necessity

⇒ The law will impliedly grant (or reserve) an easement into a conveyance of land where the parties to the conveyance held a common intention that the transferred (or retained) land would be used for a particular purpose, and that purpose is possible only if an easement is granted over the retained (or transferred) land → again, the easement is excluded by contrary intent.

⇒ "The law will readily imply the grant or reservation of such easements as may be necessary to give effect to the common intention of the parties" → "But it is essential for this purpose that the parties should intend that the subject of the grant or the land retained by the grantor should be used in some definite and particular manner" (Parker J in Pwllbach v Woodman (1915)).

⇒ See, for example, the case of Wong v Beaumont Property [1965].

The Art of Getting a First in Law - ONLY £4.99

FOOL-PROOF methods of obtaining top grades

SECRETS your professors won't tell you and your peers don't know

INSIDER TIPS and tricks so you can spend less time studying and land the perfect job

We work really hard to provide you with incredible law notes for free...

The proceeds of this eBook helps us to run the site and keep the service FREE!

(2) The doctrine in Wheeldon v Burrows

Summary

⇒ The case of Wheeldon v Burrows establishes that when X conveys (i.e. sells or leases) part of their land to Y, an easement benefiting the land transferred to Y and burdening the part retained by X will be implied into the conveyance provided that:

- Before the transfer there was a quasi-easement over the retained part in favour of the transferred part;

- At the time of the transfer, this quasi-easement was 'continuous and apparent';

- It is 'necessary for the reasonable enjoyment' of the transferred part that Y has an easement in the shape of the earlier quasi-easement.

⇒ An easement will not be implied via the doctrine in Wheeldon v Burrows if, at the time of conveyance, the parties exclude its operation

1) Quasi easement

⇒ A 'quasi-easement' is an easement-shaped practice which X engages in pre-transfer, when they own and occupy the whole of the land.

⇒ In other words, a 'quasi-easement' is a practice which would qualify as an easement if Blackacre were in separate ownership or occupation.

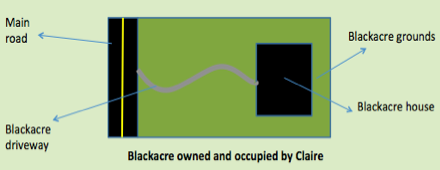

⇒ For example, say Claire owns and occupies the whole of Blackacre (above) and during her ownership she uses the driveway to get from the road to her house. In other words, during her ownership of Blackacre, Claire is acively using part of her land (i.e. the driveway) in order to benefit another part of her land (i.e. the house).

⇒ The use of her driveway on one bit of land for the benefit of another bit of land is an easement shaped practice (a quasi-easement).

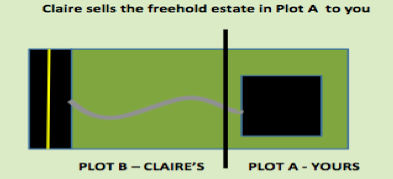

⇒ If Claire then sells plot A to you (and retains plot B), due to the quasi-easement engaged by Claire pre-transfer, implied into the transfer of plot A to you will be an easement replicating exactly the quasi-easement Claire engaged in.

2) Continuous and Apparent

⇒ For example, before land is sold to you the quasi-easement must be 'continuous and apparent'.

⇒ The requirement that the quasi-easement be 'continuous and apparent' has been reinterpreted in the courts.

⇒ In Borman v Griffith [1930], Maugham J held that a quasi-easement need not be 'continuous' in order for the doctrine in Wheeldon v Burrows to apply, but must be 'apparent' in the sense of being obvious/visible.

- Thus, the court now no longer look for the quasi-easement to be both continuous and apparent, but now just look for it to be apparent.

3) Necessary for reasonable enjoyment

⇒ The easement must be necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the transferred land.

- The easement need NOT be absolutely essential for reasonable enjoyment of the land, but just necessary for reasonable enjoyment → the definition of necessity here is different from true necessity and common intention necessity.

⇒ See, for example, the cases of Wheeler v JJ Saunders [1994] and Goldberg v Edwards [1960].

⇒ In contrast to implying an easement by necessity, easements implied by the doctrine of Wheeldon v Burrows can be granted but not reserved → "If the grantor intends to reserve any right over the tenement granted, it is his duty to reserve it expressly in the grant" (Thesiger J in Wheeldon v Burrows).

(3) The doctrine contained in the LPA 1925 section 62

General words implied in conveyances: LPA 1925 section 62(1)

⇒ This section operates to imply into every conveyance of land a range of rights and advantages relating to the land transferred i.e. relating to hedges, ditches, fences, etc. → interestingly, an easement is one of the rights and advantages that is implied into every conveyance of land.

⇒ So, by virtue of this section, the benefit of an easement passes automatically with the burdened or benefitted plot of land.

- It is very simple: if land is benefitted by an easement that benefit will travel automatically on a conveyance of that land.

- This can be contrasted with the position under restrictive covenants where, at least prima facie, the passing of a benefit of a restrictive covenant is a matter of some complexity.

- Question marks remain over whether whether the burden of an easement will pass on the conveyance of the burdened land.

⇒ But more than this, the court has used this article to imply, quite creatively, new easements into a conveyance of land.

How is section 62(1) LPA 1925 used to imply easements into a conveyance of land?

⇒ Section 62 of the Law of Property Act 1925 reiterates into a conveyance of land all "rights and advantages whatsoever... enjoyed with... the land".

⇒ Section 62 of the Law of Property Act 1925 reiterates into a conveyance of land all advantages benefiting the land conveyed and burdening the land retained.

- So when part of Blackare is sold from Claire to me, reiterated into that conveyance are all the rights benefitting the land granted to me and burdening the land retained by Claire.

⇒ When an easement-shaped advantage (right) is by virtue of this section reiterated into a conveyance of land it technically lacks the formality for its valid creation → however, when it is reiterated into a conveyance the lack of formality is repaired because the conveyance of land is necessarily made by deed (i.e. conveyance of a legal freehold or a leasehold of greater than three years) → The easement-shaped advantage is thus transformed into a fully-fledged easement.

⇒ An easement will not be implied via the doctrine in section 62 if, at the time of conveyance, the parties exclude the section's operation.

⇒ Section 62 can be used only to grant and not to reserve an easement on conveyance. This is made clear by the wording of the section: the transferee is given the advantages and not the obligations belonging to the land.

Distinguishing implication under section 62 from Wheeldon v Burrows

⇒ Both routes are similar in how they imply an easement into a conveyance of land:

- Both doctrines are implying an easement on the basis that prior to the conveyance an easement shaped practice was occurring on the land for the benefit of the land that has been transferred;

- Both operate to grant NOT reserve;

- And can both be expressly excluded.

⇒ However, Wheeldon v Burrows has additional requirements compared to section 62 → only the first of the three requirements in Wheeldon v Burrows needs be satisfied in order for implication to occur on a conveyance of land under Section 62 of the Law of Property Act 1925.

⇒ Historically, there was a further basis for distinguishing implication under Wheeldon and implication under section 62:

- The courts applied the doctrine in Wheeldon v Burrows to the situation where, prior to transfer, X both owned and occupied two plots of land. Conversely, section 62 was applied to the situation where, prior to transfer, X owned two plots of land but occupied only one of the two plots.

- The courts required this diversity of occupation to engage section 62: "The reason is that when land is under one ownership one cannot speak in any intelligible sense of rights, or privileges... being exercised over one part for the benefit of another. Whatever the owner does, he does as owner and, until a separation occurs, of ownership or at least of occupation, the condition for the existence of rights, etc, does not exist." (Lord Wilberforce in Sovmots v Secretary of State [1979]).

- The recent High Court decision of Wood v Waddington (2015) purports to collapse this second basis for distinguishing the doctrines in Wheeldon v Burrows and Section 62 of the Law of Property Act 1925.

Implied easements: legal or equitable

Summary

⇒ When an easement is implied into a conveyance of land, it assumes the formality of the conveyance.

⇒ A deed is necessary in order to convey a legal freehold or a legal leasehold exceeding three years (Law of Property Act 1925, section 52)

⇒ An easement implied into such a conveyance is therefore taken to have been created by deed.

⇒ Unlike expressly granted easements, implied easements need not be registered in order to be legal: Land Registration Act 2002 section 27(d) is limited to the "express grant or reservation" of an easement.

⇒ Where the sale or lease of the land is made by enforceable written contract (as in Borman v Griffith [1930]) the easement is equitable only (Law of Property Act, section 52; Parker v Taswell (1858)).

*Exam tip*

⇒ Make sure that you are clear about when a situation can involve Wheeldon v Burrows. A useful guide is to look for a plot of land which is originally in the ownership of one person and is then subdivided.

⇒ Some other helpful legal resources on passing the benefit of covenants:

Law Application Masterclass - ONLY £9.99

Learn how to effortlessly land vacation schemes, training contracts, and pupillages by making your law applications awesome. This eBook is constructed by lawyers and recruiters from the world's leading law firms and barristers' chambers.

✅ 60+ page eBook

✅ Research Methods, Success Secrets, Tips, Tricks, and more!

✅ Help keep Digestible Notes FREE